Sholay: Golden even after fifty years

It’s been 50 years since Sholay was released in 1975. Reflecting the undying popularity of the film, it is now ready for re-release, even adding edited out clippings and has already been enjoyed by a captive audience in Italy recently. Meanwhile movie-goers in India are eagerly waiting for its release in August. Shoma A. Chatterji goes down the memory lane with her own experience of watching it ‘first day- first show’

The year Sholay, an action-driven movie laced with violence, was released almost simultaneously the mythological super hit Jai Santoshi Maa hit the screens across India. Being an avid cine-buff, it was de rigueur to catch a new movie in a theatre the first week of its release. I watched both and was amazed at the frenzy of devotion at the Jai Santoshi Maa show.

Sholay was released at Badal, the first of the triumvirate of luxury theatres near Shivaji Park in Bombay (Mumbai) alongside Bijlee and Barkha. The three single-screen theatres have vanished into oblivion now but old-timers remember them as laying the foundation stone of the luxury multiplexes we witness today. Those were the days when people, including children, dressed in their best while coming for a film show as if they had come to a wedding reception. Children begged parents for that tempting packet of potato wafers or gola ice fruit (machine-churned coloured ice).

For Sholay we had chosen to go for the 3.00 pm show as the film, we had learnt, had a running time of 198 minutes post-censorship. There was no crowd at the ticket counter. We stepped into the nearly empty theatre, a bit uncertain if it was a bad idea to buy two balcony tickets of a dud film at a price slightly costlier than our affordability.

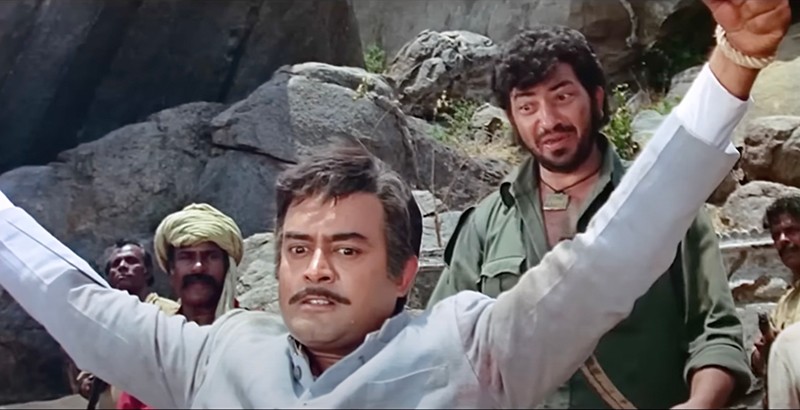

With big stars like Dharmendra, Hema Malini and Sanjeev Kumar, alongside Hangal and Satyen Kappu, this was quite surprising, though. Amitabh Bachchan was almost a newbie and Amjad Khan was an unknown entity making his debut in filmdom, which, even Ramesh Sippy doubted, if he would be a sad substitute for Danny Denzongpa, initially cast for the Gabbar Singh character. He had to turn down the offer as he had already given his dates to another director.

But after some silly ads and a boring newsreel when the film began, we sat up, our senses alert, our ears plugged to the soundtrack to catch every line of the dialogue and eyes focused on Jay, Veeru, Basanti, Gabbar Singh, Thakur and everyone else in the film. The motorcycle with a sidecar on which Veeru and Jay jump and dance and laugh at the passing country girls looked quite silly but it seemed like lots of fun.

After guffawing at the funny antics of Soorma Bhopali and the caricaturing “English ke Zamane Ke Jailor” or, Jay’s urging mausi to agree to Basanti’s marriage to Veeru, the audience turned completely silent when the young Sachin’s mare trots back to the village without its rider and his blind father says, “namaaz padne ka waqt ho gaya hai”. We were by now completely mesmerised.

Who can forget Helen’s item number Mehbooba Mehbooba offering a beautiful counterpoint to Basanti’s jab tak hai jaan number near the climax, Thakur Singh’s shawl flying away in the breeze revealing the empty sleeves of his milk white kurta as the two thieves look stunned and speechless, and, Veeru discovering that the flipping coin Jay owned had the same face on both sides?

I watched Sholay again five years later, in the company of five family members at Minerva Theatre, quite far from where we lived. But by the time we reached, three big HOUSEFULL signs were hanging outside the main gate. All tickets had been ‘sold.’

We had to buy the tickets in ‘black’ at the princely sum of Rs 100 each, turning us almost bankrupt with just enough money to take the bus ride back to Shivaji Park. In the bargain, we also became a party to the crime of ‘black’- the first and last time in our lives. But it was a decision we didn’t regret.

‘Tickets in black’ needs a little elaboration for Generation X cine buffs today. There was no online booking those days, and the cell phone was not even in our wildest dream. So, there were these smart-ass youngsters, even men and women, who would wait for the ‘Houseful’ sign to come up; Then these shady characters would make an appearance offering the same tickets at double, treble or even at four times the price, depending on the popularity of the film.

And there we were, forgetting to regret the ‘black’ price we had paid, we listened to our own heartbeats as the horses’ hoofs thundered as Gabbar Singh’s men chased Basanti and she tried to evade them riding her favourite tonga. Badal theatre, where I had first watched the film, was not equipped with a sophisticated sound system, and now at Minerva, the six track stereophonic sound system was an amazing experience.

It was a ‘sleeper hit’ ; the audience did not respond to it in the early weeks but it picked up fast and rolled on to make a phenomenon. Even Amitabh Bachchan said in an interview that he had doubts about its success.

Sholay was the first Indian film to be released in both 35 mm and 70 mm format. It was shot in 35mm, then was blown up to 70mm for the big screen experience.

If you look closely, every single department of cinema – casting, characterization, screenplay, dialogue, cinematography, music, songs, sound design, art direction, editing, location, speech patterns and language, and even costumes were worked out in detail. Gabbar Singh remains the most outstanding and memorable villain in the history of Indian cinema, his kitne aadmi the dialogue retains its menacing tone even today.

The idea for Sholay was rooted in Salim Khan’s fascination with Westerns, especially The Magnificent Seven, The Five Men Army, Once Upon a Time in the West while Javed Akhtar worked on the dialogues to flesh it out. Sholay was inspired by Akira Kurosawa's Seven Samurai.

Sholay is an out and out mainstream Bollywood film with no pretensions of being an ‘art’ film belonging to the ‘parallel’ cinema genre. So, those nourished by a rich diet of Godard, Bergman, or, Antonioni, or Ozu might have reacted to the film with the arrogant disdain they reserved for ‘Bombay’ films. ‘Bollywood’ did not exist in the lexicon of Indian cinema when Sholay was released.

But when the celluloid wonder called Sholay slowly unfolded, layer by slow layer like the peels of an onion, it made everyone - from the intellectual (Satyajit Ray included) to the illiterate, from the poor villager to the city-smart corporate guy, tilt a hat to a film that lives on in the minds and hearts of film goers even after 50 years of its first release.

(Shoma A Chatterji is a national award-winning film writer and critic)

IBNS

Senior Staff Reporter at Northeast Herald, covering news from Tripura and Northeast India.

Related Articles

It’s official! Samantha Ruth Prabhu marries ‘The Family Man’ director Raj Nidimoru in a secret Coimbatore temple ceremony

Coimbatore/IBNS: Indian actress Samantha Ruth Prabhu on Monday tied the knot with filmmaker Raj Nidimoru at a temple in Coimbatore, away from media attention.

Samantha Ruth Prabhu ties knot with Raj Nidimoru: Report

Ending weeks of speculation, actress Samantha Ruth Prabhu has married filmmaker Raj Nidimoru, according to a Hindustan Times report.

Deepika Padukone’s sister Anisha set to tie the knot! Meet her fiance with a legendary Bengali film connection

Mumbai/IBNS: Bollywood star Deepika Padukone’s younger sister Anisha Padukone is set to marry her long-time boyfriend Rohan Acharya, a Dubai-based entrepreneur, Deccan Herald reported.

Dhanush, Kriti Sanon's Tere Ishk Mein maintains strong run at box office

Mumbai/IBNS: The Dhanush and Kriti Sanon starrer Tere Ishq Mein continued its strong performance at the box office on its second day, extending its impressive opening weekend collection.

Latest News

Austrian influencer found stuffed in suitcase: Ex-boyfriend makes stunning confession

It’s official! Samantha Ruth Prabhu marries ‘The Family Man’ director Raj Nidimoru in a secret Coimbatore temple ceremony

'Was on a plane': Shashi Tharoor absent again from key Congress meet, sparks exit buzz ahead of Kerala polls

AI, robotics, and a work-free life: Elon Musk makes a bold prediction!